What Entropy tells us about Data Compression

Part II: Case Studies

Introduction

The previous article in this series, What Entropy tells us about Data Compression, described the use of Shannon entropy as a tool for evaluating the information content of a data set and assessing the effectiveness of data compression techniques. This article will take a look at various data products and discuss how the entropy of the source data relates to the data compression statistics for the results.

Note: This article is under construction. Additional information and case studies will be coming soon.

The test subjects used for these case studies are all based on raster (grid) data products giving geophysical data in a numerical form. Data of this type is the focus of the Gridfour Software Project, an open-source project that provides API's for both the Java and C programming languages.

At this time, Gridfour uses two classic data compression techniques: Huffman coding and Deflate. It also supports the use of experimental or application-specified data compression techniques, but those are outside the scope of this article. For more information on Gridfour's data compression implementations, see our article on algorithms for raster data compression.

The entropy calculation

The entropy values reported in the discussion below is based on Claude Shannon's first-order

entropy formula (Shannon, 1948). For more information on the concept of entropy, see the

previous article in this series.

Shannon's entropy formula is based on the probabilities of different symbols appearing

within a data set. For natural language text, these symbols might be letters of the alphabet.

For numeric data, they might be the values of bytes appearing in a sequence. Each such symbol

has a corresponding probability

has a corresponding probability  .

For this article, we use a variation of of Shannon's forumulation that gives us entropy H(X) as a rate

expressed in terms of bits/symbol:

.

For this article, we use a variation of of Shannon's forumulation that gives us entropy H(X) as a rate

expressed in terms of bits/symbol:

In addition to finding the entropy rate for a data product, we may also be interested in the entropy for the

product as a whole. We can treat the aggregate entropy in a data set as a simple

multiple of total number of symbols, k, in the data set (the overall length of a text, the total number

of bytes in a numeric product, etc.) times the entropy rate. Typically, the aggregate entropy, HA(X),

is expressed in bytes by including the value 8 in the denominator so that:

Case study 1: ETOPO1

The ETOPO Global Relief Model is a collection of data products that combine elevation and bathymetry (ocean-depth) data from global and regional data sets into a single raster (grid) for the entire Earth. ETOPO1 (NOAA, 2009) provides a downsampled version of the model organized in a grid with 1 minute of arc spacing, or about 1855 meters (1.15 miles) at the Equator. Major parameters related to ETOPO1 are shown below.

Data source: ETOPO1_Ice_c_gmt4.grd

File format: NetCDF (internally, HDF5)

Data type: 4-byte integers

File size: 933,120,000 bytes (original, uncompressed)

Min value: -10803 meters(Mariana Trench area)

Max value: 8333 meters (Mt. Everest area)

Range: 19136 meters [ 8333 - (-10803) ]

Raster size: 10800 x 21600 for 233280000 grid cells

Case study 1.a: Data compression

If we compress the source ETOPO1 data file using standard Deflate data compression technique, it reduces the size of the file to 288.4 MiB. Superficially, that appears to be roughly a factor of three compression ratio. But, looking at the range of values in the descriptive parameters given above, we see that a lot of the content of the source file could easily be accomodated by two-byte (short) integers rather than the four-bytes used by the source data. It is unclear why the original authors elected to store their data as four-byte integers when they could have used two-byte integers. But we do know that a lot of the byte content of the source data is just filler (either 0x00 if the elevation value is positive, or 0xff if the elevation is negative).

The entropy rate computation is driven by unpredictability in a data set. And, because the filler bytes are highly predictable, they tend to reduce the overall value of the entropy rate calculation. For example, if we compute the entropy on a byte-by-byte basis for the source data, we find an entropy rate of 4.822 bits/symbol (bits per source byte). However, if we screen out the filler bytes, we obtain an entropy rate of 7.14 bits/symbol. Removing the filler reduces the size of the data set by nearly half (not exactly half, because there is some overhead for file headers in the source data products). Again, eliminating the filler does not change the actual values of the elevations and ocean depths stored in the data product. It just changes the statistical properties of the file (not the data) and the way it is processed by conventional data compression techniques. With the adjustment for data type, we see the following specifications:

ETOPO1_Ice_c_gmt4.grd

Source format: 4-byte integers

Source size: 933,120,000 bytes (file header and overhead removed)

Entropy rate: 4.82 bits/symbol

Aggregate entropy: 562,314,013 bytes

Compressed Size: 396,162,572 bytes

Compression ratio: 2.36 to 1

Source format: 2-byte integers

Source size: 466,560,000

Entropy rate: 7.14 bits/symbol

Aggregate entropy: 416,480,740 bytes

Compressed size: 323,323,316 bytes

Compression ratio: 1.44 to 1

Comparing the two compression ratios in the example above, we see that the higher entropy for the 2-byte format results in a reduced compression ratio. On the other hand, the final compressed size for the 2-byte case has a smaller aggregate entropy and a smaller final compressed size. This difference highlights the idea that compression ratio only tells us part of the story when it comes to evaluating the effectiveness of a technique. Also, the higher entropy for the 2-byte case gives us an intuition that its content might be more significant than the content of the 4-byte case. For the ETOPO1 example, we know that that difference is due to the presence of unnecessary filler bytes. For other cases and other data products that may not necessarily be true. But, in practice, if we encounter anomalous or unexpected entropy rates, it may indicate that there are factors in the data that require further investigation.

Case study 1.b: A transformation to reduce entropy and improve data compression

In some cases, we can improve data compression by applying simple transformations on raster data. In the case of ETOPO1 elevation/bathymetry data, we observe that even though there is a considerable range of values (-19132 to 8333 meters), we expect that the difference between to neighboring values is much smaller. In fact, the average absolute value of the difference between adjacent grid cells is 21.23 meters. A number of implementations, including the TIFF, NetCDF, and Gridfour software libraries take advantage of this observation to improve data compression for raster products. Rather than storing the literal values from the source data, these implementation store the differences between adjacent values. In effect, this differencing operation is a fully invertible transformation that converts the data into a form that has lower entropy and is more readily compressed

Consider the case where we compute entropy taking whole-integer values (rather than breaking values into separate bytes). If we apply a simple differencing transformation over the ETOPO1 data set, we reduce both the range of values and the resulting entropy.

Original values:

Minimum: -10803

Maximum: 8333

Unique values: 17036

Entropy: 12.89

Differencing:

Minimum: -3252

Maximum: 3714

Unique values: 2500

Entropy: 6.38

And, as we've seen in some of the other examples in this article, reduced entropy leads to better compression:

Original values (2-byte integers):

Compressed size: 323,323,316 bytes

Compression ratio: 1.44 to 1

Differencing (2-byte integers):

Compressed size: 203,055,318 bytes

Compression ratio: 2.3 to 1

The key idea here is that the transformation does not discard data. Rather, it puts it into a form that is more readily processed by conventional data compression techniques.

For more information on the differencing transform, and other techniques used by Gridfour, see Compression Algorithms for Raster Data used in the Gridfour Implementation.

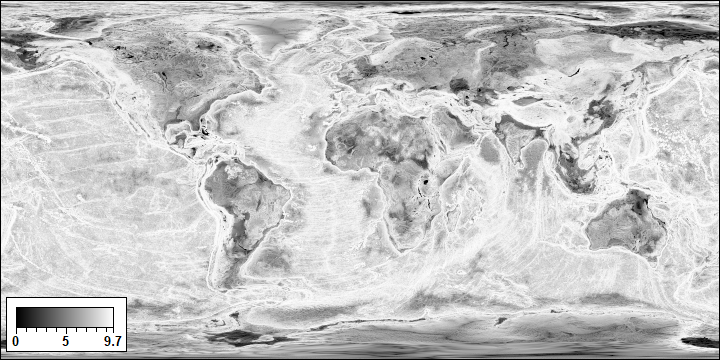

Case study 1.c: Statistical variation over the domain of a data set

The statistical properties for elevation and bathymetry data exhibit substantial variation at different locations across the Earth's surface and ocean floor. And, just as we see variations in features such as slope and surface roughness, we can also find variations in entropy. Figure 1. below shows a graph of entropy rates across the globe. Not surprising, the map shows the highest entropy rates in areas of steepest slope such as mountain ranges, the mid-Atlantic ridge, Pacific ocean trenches, and the fall off of the Continental Shelf. The ETOPO1 data set does not carry bathymetry data for Lake Victoria, one of the African Great Lakes, so it is treated as essentially flat and shows up as a black area on the map. On the other hand, ETOPO1 does include bathymetry for the Great Lakes of North America, so they do not show up as distinct features.

Each pixel in the entropy map image covers a 30-by-30 set of grid cells from the source ETOPO1 data. Entropy rates were computed for each set of cells and then used to color-code the corresponding pixel according to their values. For this analysis, we used a slightly different approach to computing entropy rates. Rather than looking at the bytes in the data set, the computation treated the full integer elevation/ocean-depth values as symbols.

The entropy rates in the figure are based on the local statistics at the area represented by each pixel. They run from 0 to 9.7 bits/elevation. When we compute entropy for the entire data set, it combines data from much different areas (flat plains, to high mountain ranges, to deep ocean trenches). So the overall computed entropy is 12.89 bits/elevation value.

Data compression techniques use the statistical properties of source data (entropy and others) to develop a compact form for their output. The figure above illustrates the fact that these statistics are not constant across the entire data product. So a data compression specification that works well over one part of the Earth will not necessarily be optimal in another.

Localized selection of compression method

For ETOPO1, the current Gridfour implementation divides the overall grid into smaller subsections called tiles consisting of 90 rows and 120 columns each (covering 1.5 degrees of latitude and 2 degrees of longitude). The Gridfour API selects either Deflate data compression or Huffman coding depending on which produces the smallest output. This approach yields the following:

ETOPO1_Ice_c_gmt4.grd

Raster size: 10800 x 21600 for 233280000 grid cells

Tile size: 90 x 120 (21600 tiles consisting of 10800 grid cells)

Compression method usage:

Deflate: 64 % of all tiles

Huffman: 36 % "" ""

Average entropy of source data as selected for method:

Deflate: 6.16 bits/elevation

Huffman: 5.83 "" ""

The fact that the Huffman method was selected so often was unexpected because the Deflate technique usually outperforms Huffman by a substantial margin. Seeking a reason for this result, we posted a notice on Stackoverflow asking When would Huffman coding outperform Deflate?. Mark Adler analyzed our sample data and determined that, while Deflate's internal Lempel-Ziv (LZ77) string matching found a large number of repeated sequences in the sample, most of them were of a very short length and led to a "negative gain" in compression. In such cases, the Deflate library does implement the ability to internally revert to Huffman coding. But the Java API we used for testing did not automatically support that option. When we enabled it, Deflate's implementation of the Canonical Huffman code usually outperformed the implementation from the Gridfour software library.

For more information on the data compression logic used to produce these results, see Compression Algorithms for Raster Data used in the Gridfour Implementation.

Case study 2: ETOPO 2022, a floating-point raster data set

Claude Shannon's definition of entropy is broad enough to include a variety of different data types. So far, we've considered character sets, bytes, and integers. Now we'll turn out attention to 32-bit floating-point data.

The ETOPO 2022 family is a successor to ETOPO1 (NOAA, 2022). It features raster data products configured to various resolutions, including a one minute of arc product with the same dimensions as ETOPO1. In addition to updating the overall data collection from ETOPO1, ETOPO 2022 introduces the use of non-integral floating-point data for elevations.Obtaining the set of probabilities for the entropy calculation for floating-point data is more involved than it was for byte and integer based products. To collect probabilities for a byte based product, we simply created an array of 256 counting elements and looped through the source data to tabulate the number of times each unique byte value showed up in the product. For two-byte integer values, we needed an array of 65,536 counters, a size which was still managable. But tabulating counts for a four-byte floating-point data type would require over 4 billion counters, a size that might even exceed the memory available for use on a large server.

There are numerous technologies available for handing very large data sets, but since this investigation was conducted in support of the Gridfour Software Project, we elected to use the Gridfour Virtual Raster Store API (see GVRS: a Fast, File-Backed API for Managing Raster Data). Both the Java and C versions of the Gridfour library include a module named EntropyTabulator that computes entropy using the following steps:

- Accept as input a GVRS-packaged version of the source-data product (such as ETOPO1 2022)

- Create a temporary virtual raster file with dimensions 65536-by-65536 (the range of an unsigned two byte integer)

- For each value in the input file

- Extract the bitwise equivalent, K, of the floating point value as a 32-bit integer

- Populate row with the two high bytes of K using row = (K>>16) & 0xffff

- Populate column with the two low bytes of K using column = K& 0xffff

- Read integer count at grid position (row, column), increment it by one, and store new count

- Add one to a running count, n, the total number of data values in the source product

- For each cell in the GVRS raster file

- Read the count value, c

- For non-zero counts, compute the probability, p = c/n, and use it as a summand term, p×log2(p), for the entropy formula

For the ETOPO 2022 variation with one-minute of arc spacing, the EntropyTabulator application reported the following:

Input:

File: ETOPO_2022_v1_60s_N90W180_surface.nc (NetCDF format)

NetCDF source file, compressed size: 478.3 MB, 16.40 bits/elevation

GVRS packaged file, compressed size: 418.0 MB, 15.04 bits/sample

Survey Results:

Elevation Samples: 233,280,000

Unique symbols: 55,054,310

Used once: 30,114,654

Used multiple times: 24,939,656

Max count: 44,466

Entropy rate: 21.10 bits/sample

Aggregate entropy: 615.4 MB

The original NetCDF format file from NOAA features a built-in data compression that reduces its size from the 32 bits per elevation used by an uncompressed floating-point value to about 16.4 bits per elevation. The GVRS compressed size is 15.04. Note that both of these sizes are smaller than the tabulated entropy for the file. This result indicates that the compression implementations for both data formats are reasonably effective.

References

Amante, C. and B.W. Eakins, 2009. ETOPO1 1 Arc-Minute Global Relief Model: Procedures, Data Sources and Analysis. NOAA Technical Memorandum NESDIS NGDC-24. National Geophysical Data Center, NOAA. doi:10.7289/V5C8276M. Accessed 15 November 2024.

NOAA National Geophysical Data Center. 2009: ETOPO1 1 Arc-Minute Global Relief Model. NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information. Accessed 15 November 2024.

NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information. 2022: ETOPO 2022 15 Arc-Second Global Relief Model. NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information. DOI: 10.25921/fd45-gt74. Accessed 15 November 2024.

Shannon, C. (July 1948). A mathematical theory of communication (PDF). Bell System Technical Journal. 27 (3): 379–423. doi:10.1002/j.1538-7305.1948.tb01338.x. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-002C-4314-2. Reprint with corrections hosted by the Harvard University Mathematics Department at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harvard_University (accessed November 2024).